A reader* responds to “Science, Suffering, and Shrimp”:

>we may just always disagree on the likelihood of invertebrates feeling morally significant suffering

Au contraire!

There is nothing about a vertebrate that inherently leads to consciousness, and there is no reason to believe that consciousness is limited to vertebrates.

The analysis of what we know about shrimp can not be extrapolated to all invertebrates. Indeed, one of the meta studies cited in the shrimp review tends to lean toward lobsters being able to experience pain.

Indeed, if I had to bet Anne’s life (the highest stakes, as that would also be betting my life), I would say that octopuses can have conscious, subjective experiences. I think it is more likely that octopuses can feel morally significant suffering than vertebrate fish.

I am not sure about any of this. It seems impossible to be 100% certain when it comes to any question regarding consciousness in another. For example, there seems to be no way to know that I’m not just a simulated mind being fed inputs. (I wouldn’t bet on it, but it isn’t impossible. When was the last time you knew a dream wasn’t “real,” no matter how weird it was?)

As I quote Sam Harris in Losing: “Whatever the explanation for consciousness is, it might always seem like a miracle. And for what it’s worth, I think it always will seem like a miracle.”

I’ve written a lot about consciousness in this blog and in Losing, but here is a very short bullet list of what I currently think:

- Consciousness is not an inherent property of reality; i.e., panpsychism is wrong and logically silly (p. 93). I’m joking about electrons, a reductio ad absurdum of thinking morality can be expected value (more on this in Part 2).

- But in fairness to the epiphenomena / zombie crowd, consciousness really isn’t required for much of behavior we see in creatures we assume to be conscious. (e.g., “Robots won’t be conscious”)

- Speaking of robots, I highly doubt that consciousness is substrate-specific. But I agree with Antonio Damasio that it is not enough to just create a silicon-based neural net. See the well-chosen excerpts here.

- Consciousness does not arise from the ability to sense (sunflowers sensing the sun, amoeba sensing a chemical gradient, nematodes sensing a “harmful” stimulus.)

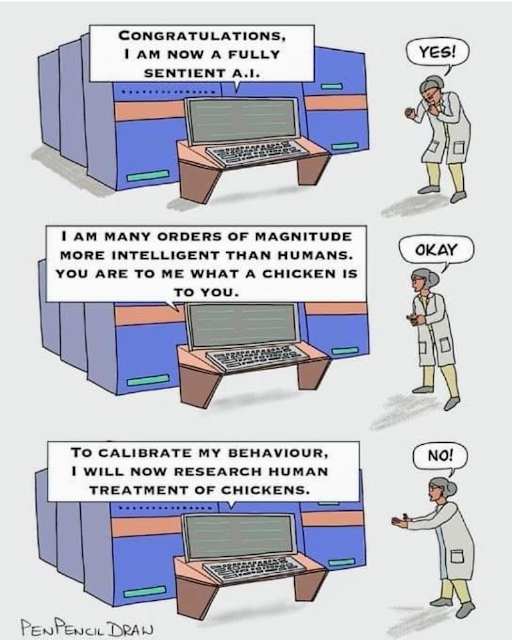

- Consciousness is not the same as intelligence.

- Consciousness isn’t binary; the simplest conscious creature does not have the same level / intensity of subjective experiences as the most complex conscious creature.

- Consciousness is an evolutionarily-useful emergent property of a certain level and organization of neural complexity. The amount of neural complexity required for consciousness is costly, so it must serve some purpose to make it worthwhile. (The Ed Yong excerpt from here is reproduced below.)

- Consciousness can serve a purpose worth its cost under certain circumstances:

- A creature is long-lived enough such that learning and adapting is beneficial.

- A creature’s behavior has enough plasticity that suffering and the pursuit of pleasure can significantly alter the creature’s life to improve their genes’ propagation. E.g., they can make difficult trade offs, like forgoing eating or mating in order to survive longer. (Again, see the Yong excerpt below.)

So no, I don’t think only vertebrate carbon-based animals can be conscious, and I don’t think all vertebrates have morally-relevant subjective experiences.

But this doesn’t mean we don’t have a disagreement! That’s Part 2.

I know that, with the links, this is all a lot (consciousness has been my intellectual obsession for well over 40 years now – it is the most miraculous thing, IMO). But just two more links, and then Ed Yong’s excerpt (and then the * footnote):

Consciousness, Fish, and Uncertainty

from Ed Yong's wonderful An Immense World:

We rarely distinguish between the raw act of sensing and the subjective experiences that ensue. But that’s not because such distinctions don’t exist.

Think about the evolutionary benefits and costs of pain [subjective suffering]. Evolution has pushed the nervous systems of insects toward minimalism and efficiency, cramming as much processing power as possible into small heads and bodies. Any extra mental ability – say, consciousness – requires more neurons, which would sap their already tight energy budget. They should pay that cost only if they reaped an important benefit. And what would they gain from pain?

The evolutionary benefit of nociception [sensing negative stimuli / bodily damage] is abundantly clear. It’s an alarm system that allows animals to detect things that might harm or kill them, and take steps to protect themselves. But the origin of pain [suffering], on top of that, is less obvious. What is the adaptive value of suffering? Why should nociception suck? Animals can learn to avoid dangers perfectly well without needing subjective experiences. After all, look at what robots can do.

Engineers have designed robots that can behave as if they're in pain, learn from negative experiences, or avoid artificial discomfort. These behaviors, when performed by animals, have been interpreted as indicators of pain. But robots can perform them without subjective experiences.

Insect nervous systems have evolved to pull off complex behaviors in the simplest possible ways, and robots show us how simple it is possible to be. If we can program them to accomplish all the adaptive actions that pain supposedly enables without also programming them with consciousness, then evolution – a far superior innovator that works over a much longer time frame – would surely have pushed minimalist insect brains in the same direction. For that reason, Adamo thinks it's unlikely that insects feel pain. ...

Insects often do alarming things that seem like they should be excruciating. Rather than limping, they'll carry on putting pressure on a crushed limb. Male praying mantises will continue mating with females that are devouring them. Caterpillars will continue munching on a leaf while parasitic wasp larvae eat them from the inside out. Cockroaches will cannibalize their own guts if given a chance.

*Another reader responded to the Shrimp post by berating me for refusing to spend a penny to save hundreds of shrimp from a “torturous” death. So if you're keeping score, one of the loudest shrimp “advocates” actively misrepresents scientific studies, and the other resorts to bullying via absurd hyperbole.