Tobias, the brains at Vegan Strategist, recently did an extended interview with me, which I'm reproducing here. Thanks to Tobias, and to EK and Anne for helping me with my draft answers.

VS: How would you define a vegan? A vegan diet?

MB: Before considering this question, I think it is important to step back and consider what is happening in the real world. Hopefully, it could help put the focus on what really matters….

You could argue that Jane’s brothers had it better. Andy and Bruce and Gene and Martin were tossed into a bag, on top of hundreds of others. Over many agonizing minutes, they were crushed as more and more were added to the bag. With increasing panic, they struggled with all their might to move, to breathe, as their collective weight squeezed the air from their lungs. No matter how desperately they fought and gasped, they couldn’t get enough air, until finally, mercifully, they blacked out and eventually died.

Jane’s torments were just beginning, however. Her mouth was mutilated, leaving her in so much pain she couldn’t eat for several days. One of her sisters was unable to eat and starved to death. Jane ended up stuffed into a tiny wire cage with Becky, Arlene, Megan, Tracy, and Lynn. To call it a “prison” would be a gross understatement. They were crammed into the cage so tightly that the wires rubbed their skin raw. Their excrement mixed with that of thousands of others, and the horrible ammonia stench of the piles of feces burned their nostrils and lungs.

Struggling for freedom, Megan was eventually able to reach her head through the wires. But then she was trapped, unable to get back in. Over the next few days, she slowly, painfully died of dehydration.

After over a year of this torture, Jane’s feet became tangled in the wire mesh of the floor. Unable to move, she was beginning to dehydrate. But before death could end her pain, she was torn from the cage, her entangled toes left behind, ripped from her body. The brutality of her handler crushed many of her bones, and she was thrown into a truck. For the next 14 hours, she and hundreds of others were driven through the Iowa winter, without protection, food, or water. The cold numbed the pain of Jane’s mutilated feet, but not the acute agony of her shattered bones. She was then shackled upside down, and had her throat cut. That’s how her torment ended.

An unfathomable number of individuals have suffered and are suffering just as Jane did.

Given that this is the current reality, we have a difficult choice to make:

We can spend our very limited time and resources worrying about, arguing about, and attacking each other over words and definitions.

Or we can focus our efforts entirely on actually ending the system that brutalizes individuals like Tracy and Gene.

If we take Jane’s plight seriously, the best thing most of us can do at the moment is help persuade more people to buy cruelty-free foods. As tempting as it is, we can’t just remain in our bubble, liking and retweeting what our fellow advocates say. We can’t be distracted by online debates. We can’t endlessly reevaluate every question and debate.

Instead, we have to focus on realistic strategies that start to create significant and lasting change with new people in the real world. As hard as it is, we absolutely must stop paying attention to people who want to create the world’s smallest club, and start paying attention to what actually creates real change with people who currently don’t know about Jane’s plight.

Questions like the above – about our definitions and opinions – seem harmless. But not only do they waste valuable time and resources, they reinforce the idea that our work is an academic exercise. It isn’t – the lives of individuals like Tracy and Andy depend on us actually doing constructive work in the real world.

VS: Do you think it is useful for vegans to point it out when they see non-vegan behaviour of “vegans”?

VS: Do you think it is useful for vegans to point it out when they see non-vegan behaviour of “vegans”?

Three things should guide our actions in any situation:

1. The behavior or practice we see has actual, real-world negative consequences for animals.

2. We have a realistic expectation that our actions will lead to a net good; i.e., there is reason to believe positive change is likely, and it is unlikely there will be any offsetting negative or contrary consequences.

3. There is nothing better (i.e., more likely to reduce more suffering) we could be doing with our limited time and resources.

2. We have a realistic expectation that our actions will lead to a net good; i.e., there is reason to believe positive change is likely, and it is unlikely there will be any offsetting negative or contrary consequences.

3. There is nothing better (i.e., more likely to reduce more suffering) we could be doing with our limited time and resources.

It is hard to imagine anything we could do that that would have fewer real-world positive consequences for animals than spending our limited time and resources policing the world’s smallest club.

I’ve actually found a pretty clear distinction between people whose primary concern is the purity and exclusivity of their club, vs those who are really working to change the world for animals. The former view everyone as the enemy. The latter view everyone as a (current or potential) ally.

Viewing everyone as an ally is not only necessary for truly helping individuals like Jane and Andy, but it is also much better for our mental health and the sustainability of our activism.

VS: What are some exceptions you would make? Is there non-vegan behaviour you indulge in?

In an interview many years ago, someone* was infuriated that I had once said I wouldn’t police what our daughter ate birthday parties. They justified their anger by saying it would send “mixed messages” if a four-year-old ate a piece of non-vetted cake. I replied that I never knew anyone who said, “Oh, I would have stopped eating animals, but then I saw this toddler having cake!”

You (Tobias) have wisely pointed out that what we personally consume is nowhere near as important as the influence we can have in the wider world. So I think our limited time is better spent figuring out how to be better examples and advocates, rather than trying to be ever more “pure.” And even if we don’t agree with that, the only way to be truly pure is to be dead. But really, is the best case scenario for the world one where I’m dead? Where you’re dead? It would be really sad if that were the case.

The evidence doesn’t support that, though. By being a thoughtful, realistic, positive, bottom-line focused advocate, we can have a significant impact beyond what we accomplish with our personal purchases.

There is so much each one of us can do to lessen the amount of suffering in the world, to expand our circle of compassion, to bend the arc of history toward justice.

But making the world a better place has to be our fundamental goal. We can’t be motivated to follow some dogma or comply with some definition. To create the change necessary to make the world a better place, we have to deal with others where they are. We have to be realistic about what change can happen and how it can most likely be brought about. We have to be pragmatic in evaluating our options and choosing the best course of action, given the variables and uncertainties inherent in the real world.

The best thing I can do in one situation (e.g., a child’s birthday party) might not be the best I can do in another situation (e.g., meeting with a group of new activists). And neither of these might be the best thing you could do in the opportunities you encounter. I can’t know for sure what the best thing to do is in any situations, but I do know it isn’t simple.

*I am happy to say that this interrogator and I are now friends, and she now regrets asking that question years ago.

VS: To what extent should we use the word “vegan” in our outreach and to what extent other words? When? What words?

I stopped eating meat, eggs, and dairy over a quarter century ago. At the time, and for years after, I was mindlessly pro-“vegan.” Not pro-animal, or pro-compassion, or pro-change. Pro-“vegan.” The word. The identity. The philosophy and “lifestyle.”

But in the real world, “vegan” is a stereotype, a punchline, an excuse. People say, “I could never be vegan,” and that is the end of the conversation – the end of any opportunity for constructive engagement, for steps taken that could have a real-world benefit for animals.

“Vegan” is an ego-boost, a divider, a distraction. It is too easy to simply judge things as “vegan / not vegan,” instead of focusing on cruelty to animals, working to end factory farms, and having any real impact in the real world.

When I focused on “vegan,” instead of how to bring about real change for animals in the real world, I was being both self-centered and lazy. I understand the desire to only care about “vegan,” of course. But at best, the word distracts from doing our best to help new people make compassionate choices that have real consequences for animals.

VS: You have said that the greatest hindrance to the spread of veganism … is vegans themselves. Can you elaborate?

I’ve seen the dynamic of “I could never be vegan” play out for years. As discussed in The Accidental Activist, bottom-line-oriented activists experience a huge increase in the quantity and quality of conversations when they changed their shirts (stickers, etc.) from “Ask me why I’m vegan” to “Ask me why I’m vegetarian.”

University of Arizona research in early 2015 bears this out: non-vegetarians see “vegan” as impossible, and “vegans” as angry, fanatical, and judgmental. I have known several individuals who have given up lucrative careers to dedicate themselves to farm animals, and yet been so put off by the actions of “vegans,” that they want to disassociate themselves from the word. This is depressing, but it’s reality. I believe it is better to face reality and adjust so we can really help animals in the real world.

VS: Do we need to guard a definition or some line? Is that important? Is there a danger of watering down the concept of “veganism”?

It can be utterly addictive to debate terms, argue philosophy, and defend positions. It can be next to impossible to turn away from a debate, given that we each think we are right, and should be able to convince someone if we get the next post just right.

In the end, though, we have limited time and resources. We can, of course, spend this limited time trying to convince someone who has wedded their sense of self-worth to a specific position. But this is no more constructive than spending our time arguing with our Uncle Bob. I think we should spend our limited time and resources reaching out, in a constructive way, to new people – people who actually could make a difference with better-informed choices.

As difficult as it is, it would be so amazing if everyone who reads your blog would stop engaging in internecine debates. Ignore the attacks. Ignore the name calling. Give up the fantasy of winning an argument. Give up any concern with words or dogma. It would be so incredible if we were to just focus on positive outreach to new people.

VS: For most of your career, you have mainly worked on person-to-person outreach, rather than institutional outreach. What is the reason behind that?

When I stopped eating animals back in the 1990s, there was really no consideration of doing institutional outreach regarding farm animals. Before I did a more utilitarian evaluation of my efforts, I did try to put pressure on Procter and Gamble to stop testing their products on animals, even going so far as to get arrested.

After that, though, I realized I needed to work where I could have the biggest impact in terms of reducing suffering. But I couldn’t just go to a restaurant or food service provider and ask them to add in more cruelty-free options. This is a capitalist society, and if the demand isn’t there, no company is going to create supply (this played out when some McDonald’s introduced a veggie burger years ago, and it failed). Similarly, I would have no impact as an individual in asking Smithfield or Tyson to stop using gestation crates or move to a less cruel slaughter method.

Things have changed significantly in the past three decades. The animal advocacy movement as a whole has gained significant political and market power, such that corporations are more likely to listen and cooperate. Demand for meat-free options has grown in breadth (if not depth) such that working with institutions can have a lasting impact and further drive the cruelty-free demand / supply cycle. There is so much potential – more than half of the people in the US are specifically concerned with the treatment of farm animals!

Some of the most important and consequential work being done right now is at the institutional level. e.g. banning the most barbaric practices from factory farms, increasing the availability of cruelty-free options, and building the companies that will create the products that will replace animal products.

But as long as people want to eat an animal’s flesh, animals will be treated like meat. Of course, this isn’t saying that all animal exploitation is equally bad, or that abolishing gestation crates or battery cages isn’t an important step forward.

What we do know, however, is that even in “humane” meat situations, there is suffering – often, egregious cruelty. We’ve seen this regularly, including PETA’s recent exposure of the horrors of Whole Foods “humane meat.”

The continuing necessity of work on the demand side, combined with my background and opportunities to date, leads me to conclude that at this moment, I can have the biggest impact on the advocacy side. I don’t know if this will continue to be the case, however. There is a ton of exciting work going on now that wasn’t the case even 10 years ago!

VS: What do you think of reducetarian outreach?

The reducetarian approach is rooted in one vitally important psychological insight: people are more likely to attempt and maintain a change that seems achievable, rather than something that seems far beyond where they are now. This has been shown over and over again – not only that the more realistic a change is, the more likely people are to attempt it, but also that the more stepwise a change, the more likely people are to maintain that change.

But as currently embodied, the reducetarian movement misses another important psychological truth (as discussed by Dr. Gordon Hodson): goals must be not only reasonable and achievable, but clear. “Eat less meat” is not a clear goal. Reach out to just about anyone considered to be a likely target for dietary change and ask them to “eat less meat,” and they will almost universally reply, “Oh, I don’t eat much meat.”

They often add, “Just chicken.” But of all the factory-farmed animals brutalized and killed for food, the vast majority are birds. Yes, nearly everyone cares more about mammals than birds. But as Professor of Veterinary Science John Webster has noted, modern poultry production is, “in both magnitude and severity, the single most severe, systematic example of man’s inhumanity to another sentient animals.” Combine this with the fact that it takes more than 40 chickens to replace the meals produced by one pig, and more than 200 birds to replace one cow, everyone who “eats less [red] meat” and replaces even a little of it with birds is causing a lot more suffering.

Like doctors, our first duty as advocates should be to “do no harm.” The initial test we should run on any potential campaign or message is, “Is there any chance that my efforts will actually lead to more animals suffering in the real world?” Unfortunately, I think the “eat less meat” campaign might fail that test.

VS: Speaking of chickens, in 2014, you helped create One Step for Animals, which emphasizes decreasing chicken consumption. It’s clear that that would help save a lot of lives and suffering (as chickens are both such small animals and so intensively raised). Do you think there’s any truth to the idea that this is speciesist, or that it encourages eating other animals?

VS: Speaking of chickens, in 2014, you helped create One Step for Animals, which emphasizes decreasing chicken consumption. It’s clear that that would help save a lot of lives and suffering (as chickens are both such small animals and so intensively raised). Do you think there’s any truth to the idea that this is speciesist, or that it encourages eating other animals?

Encouraging people to cut back on or not eat chickens is just that. It is in no way saying that people should eat cows, or pigs, or dogs, or chimpanzees.

One Step isn’t concerned with speciesism, but rather, realism. One Step takes starts with all the statistics and known psychological truths. Just as importantly, though, One Step refuses to be driven by definitions. One Step refuses to engage or appease the dogmatists. Rather, One Step for Animals is concerned only with results in the real world: reducing the most suffering possible. You can disagree that their approach is likely to do that, but “reducing suffering” is the only metric by which One Step (or any group) should be judged.

VS: What is the number one piece of advice you would give to vegan activists?

Rather than considering how popular something is with your circle of friends, judge everything by the likely consequences your actions will have with non-vegetarians in the real world. To a first approximation, this will mean calculating how your actions will impact people’s consumption of chickens.

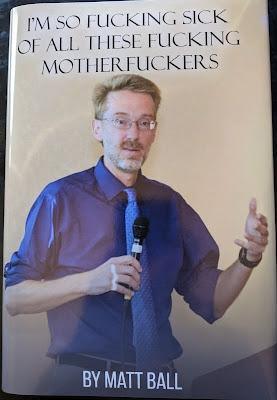

For more tips and suggestions, people can check out my books and writings:

If you like a linear discussion, The Animal Activist’s Handbook is probably your best bet.

If you like a linear discussion, The Animal Activist’s Handbook is probably your best bet.

|

| I own the only copy of this |

If you like collections of essays and short stories, The Accidental Activist.

If you don’t want to buy a book, A Meaningful Life is a good start.

No comments:

Post a Comment